An elementary school teacher, Rose-Anne had been about to welcome a guest speaker to her class up the street when a call came in to the school office. In a heart-pounding drive it took Rose-Anne McLellan, Nathaniel’s mom, less than four minutes to get to the hospital, her son in the back seat of the Yukon. The little boy was so rigid she could not buckle him in place. A woman with a mass of dark curls jumped out, had a brief conversation on the sidewalk with the woman pulling the wagon, then grabbed the child from her arms, draped his stiff form over the bucket portion of a child’s car seat, banged the door shut and raced off.

“Why is the little guy not in the wagon?” Al wondered as he pulled into his driveway.īehind Al, out of his sight, a white GMC Yukon SUV drove up the road and slammed to a stop. It was a cold day, and the little boy the woman was holding was not wearing shoes or a coat. Al continued slowly past, then signalled and turned the corner on the way to his house, a hot pizza box on the passenger seat, lunch for him and his wife. Ahead, a second child zigzagged across driveways and up onto front lawns. Her other arm was wrapped under the armpits of a child who was facing outwards, upper body buckled over her arm.

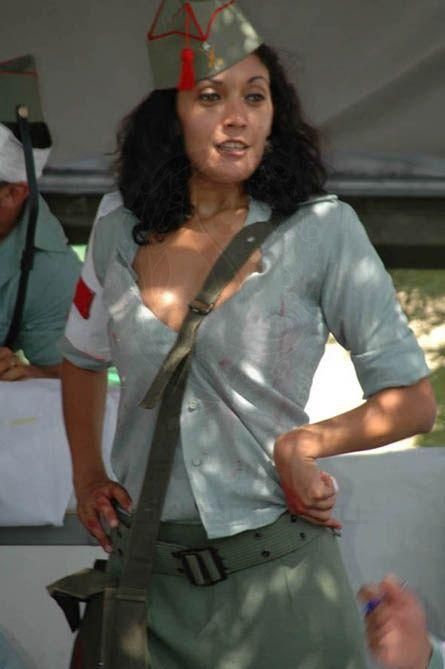

With one arm, the woman was pulling a red wagon. Strathroy, a small town in southwestern Ontario, had been home for his whole life and he was pretty sure he recognized the woman. “Hang on, hang on,” he muttered to himself, braking slightly. The way the woman on the sidewalk was holding the little boy looked wrong. Passing by in his car, Al felt it in the pit of his stomach, a sinking feeling that has never gone away more than five years later. Something looked out of whack to Al Azevedo later that fall morning in 2015, a few days before Halloween. Dad owns a heating and air conditioning business. Drop Nathaniel, the youngest, at the new daycare. Out the door and down the gravel lane to the yellow school bus.

0 kommentar(er)

0 kommentar(er)